On the supremacy of the spiritual powers over the powers of states and statesmen - the Searches in the Philosophy of Religion - 12:39 AM 1/4/2020

If Islam Is a Religion of Violence, So Is Christianity ...

_______________________________________________

Веленью божию, о муза, будь послушна,

Обиды не страшась, не требуя венца,

Хвалу и клевету приемли равнодушно,

И не оспоривай глупца.

Я памятник себе воздвиг нерукотворный...

Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (1799—1837)

________________________________________________

On the supremacy of the spiritual powers over the powers of states and statesmen - The Searches in the Philosophy of Religion - By Michael Novakhov

Contents

1. Christianity is Culture, and our modern Western Culture is Christianity

2. The Christendom is dead!

3. Searches in the Philosophy of Religion

4. The Supremacy of the Spiritual Powers

5. The Papal Supremacy

6. Other Related Searches

____________________________________

On the supremacy of the spiritual powers over the powers of states and statesmen - the Searches in the Philosophy of Religion

By Michael Novakhov

Introduction: The powers of the Divine compelled me to search for answers

To my opponents I should dedicate this little piece of thought: they should be viewed in the magic mirror of irony as the angelic part of my devilish Self.

A man knocked on my door yesterday evening; he was sent by those in power; they are puzzled by me, and want to coopt me, forgiving kindly all the insults and the endless series of wrath that I hurled at their poor bold heads in my angry impatience, deservedly or not.

"You look like a priest, pray for me", I told that man half-mockingly, and slammed the door in his face. And now I feel guilty about my rudeness. And this prompted me to compile this Search, as a note and the greeting to those who sent that nice man, and as my penitence, but without changing the substance of the response: there is no way, that this independent and rebellious Spirit of mine can be coopted by anything or anyone. The Island is an Island and forever an Island. And the Islands are always lonely; that's their nature, I guess.

I questioned the men in power, rather arrogantly, earlier: Where are your Theologians, I asked them, and what did they produce? And it was I, the absolute, laughing, teasing, condescending NON-BELIEVER!

And now the Powers of the Divine compelled me to search for answers, as ironically as it sounds.

See also:

Organic or Organismic Theory

Organic or Organismic Theory of Society

_______________________________________________

On the

over the

By Michael Novakhov

1. Christianity is Culture, and our modern Western Culture is Christianity

Und why iz ziz zo? That'z zi Question!

In brief, because the State Powers are concerned with the large social structures, their self-organisations, functioning, preservation, expansions, and perpetuation; just like the physical human bodies, their atomic units, are concerned with the same tasks and issues.

Spirit governs these bodies, makes them alive and unique, and is ultimately endlessly and boundlessly free, and that is why it has the supreme power over them, and it practices and exercises these powers in the ways visible and invisible, fleeting and determined. This Spirit is Culture.

Christianity is Culture, and our modern Western Culture is Christianity, first of all, and most of all, as its most defining component and element.

2. The Christendom is dead!

Pope Francis on the end of the Christendom

Pope Francis on the end of the Christendom - Google Search

Search Results

'Christendom no longer exists,' pope says, explaining need to revamp Curia

As he has often done, Pope Francis quoted the 19th-century composer Gustav Mahler, who said, "Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire."

"Christendom no longer exists," he said. "Today we are not the only ones who produce culture, nor are we the first or the most listened to."

Christianity, "especially in Europe, but also in a large part of the West, is no longer an obvious premise of our common life, but rather it is often denied, derided, marginalized or ridiculed."

"In all its being and acting, the church is called to promote the integral development of the human person in the light of the Gospel," he said.

The church does so, he continued, by "serving the weakest and most marginalized, in particularly forced migrants, who represent at this time a cry in the desert of our humanity" and are "the symbol of all those thrown away by our globalized society."

The church, he said, "is called to testify that for God no one is a 'stranger' or 'excluded.' It is called to awaken consciences numbed by indifference to the reality of the Mediterranean Sea, which has become for many, too many, a cemetery."

| National Catholic Reporter

As Robert Mickens wrote in a 2018 piece for La Croix, "Vatican Godfather," Sodano worked quietly to push cardinal electors behind Bergoglio.

"For some three decades he was the man in the Vatican no one dared to cross," wrote Mickens. "Even the popes he served were careful to gain his consent because of the loyalty he commanded from many key people at all levels of the Roman Curia."

M.N.: I wrote so many critical things about Cardinal Sodano, (and just like so many other reporters and writers, who at times were even more critical than I was), and I called him "Cardinal Satano", but if I were there at that moment, I would him a big bear hug, without any hesitations, and absolutely sincerely, so great is the mysterious power of this man. Even at his age of 92, he looks sharp, smart, wise (in many meanings, probably), fatherly, understanding, forgiving, priestly, grand, but with a certain devious tinge.

Pope Francis greeting Cardinal Angelo Sodano. (Vatican Media)

Things are complex, and the name callings do not solve the problems. I wish, he would tell us his story, and nothing but the truth. He definitely knows a lot, and definitely the stuff we all can learn from. And he can share it with us, if he so chooses.

Do this, Bro - Fra, tell us. We do want to learn from you, good and bad, beautiful and ugly, the Godly, the Divine, and the Earthly and the Devilish. But the whole TRUTH. I know, if he tells his story, he will tell the whole truth, I would trust him with this.

Do this, Bro. Do this, Grandpa.

See also: Cardinal Sodano - Google Search

______________________________________________

Pope Francis made the huge, "epochal", historical announcement and the admission, which, was just the recognition, acceptance, and the official acknowledgement and statement of the obvious fact, formed and shaped naturally during the past century:

The Christendom is dead!

Long live the true and the renewed Christianity and the Great Western Culture and Civilization!

Long live the true and the renewed Christianity and the Great Western Culture and Civilization!

It took the extraordinary courage and the sense of historical responsibility to make this admission. The "Cristendom", this historically formed conglomeration of the Empires, Kingdoms, Czardoms, various Principalities, etc., etc., is no more!

What is left, is pure and purified, cleansed, transformed, renewed, revitalized, Divinely Cured in the Magnificent Halls of CURIA, the True CHRISTIANITY, which is the Empire and the Dominion of SPIRIT, unbound and free, at the long last. The Spirit Of Christianity shed away the vestiges of its service and subservience (if it ever was so) to the Earthly and State Powers. From now on, as it was declared, Christianity exists in the form of Culture, and the Western Civilization and Culture in their essence, in their hearts of hearts, is the Christianity.

And the "WP": the Word Power, the Power of verbal self-expression, Religious Thought and Word, the Literature and the Humanities, in this new age of the Internet and the Social Media, have increased greatly, and became the new shaping social and political force to be reckoned with.

And the "WP": the Word Power, the Power of verbal self-expression, Religious Thought and Word, the Literature and the Humanities, in this new age of the Internet and the Social Media, have increased greatly, and became the new shaping social and political force to be reckoned with.

The Papal Supremacy became truly supreme, omniscient and omnipresent, it became the renewed and the redefined Spiritual Supremacy, and in this Divine Transformation, paradoxically, if you will, it acquired more Powers, and more efficient, and more effective Powers, among them, the Powers to influence the peoples' hearts and minds, and therefore to influence and to shape the World events and developments.

The Pope's authority became the ultimate Global Moral Authority and Power, reigning supreme over all the other Powers, and dictating and ruling over them.

Mazel Tov, Pope Francis! And I am absolutely, 100% serious about this congratulation, and about everything I have described and interpreted so far.

The new Epoch has truly started, and not just the New Year and the New Century, but the New Millennium!

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

3. Searches in the Philosophy of Religion

Philosophy of Religion - Google Search

Philosophy of religion is the philosophical study of the meaning and nature of religion. It includes the analyses of religious concepts, beliefs, terms, arguments, and practices of religious adherents. The scope of much of the work done in philosophy of religion has been limited to the various theistic religions.

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such ...

Philosophy of religion, discipline concerned with the philosophical appraisal of human religious attitudes and of the real or imaginary objects of those attitudes, ...

Philosophy is the most critical and comprehensive thought process developed by human beings. It is quite different from religion in that where Philosophy is both ...

A brief introduction to some of the issues discussed in the Philosophy of Religion and Natural Theology.

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Mar 12, 2007 - Philosophy of religion is the philosophical examination of the themes and concepts involved in religious traditions as well as the broader ...

People also search for

Philosophy of Religion

First published Mon Mar 12, 2007; substantive revision Tue Jan 8, 2019

Philosophy of religion is the philosophical examination of the themes and concepts involved in religious traditions as well as the broader philosophical task of reflecting on matters of religious significance including the nature of religion itself, alternative concepts of God or ultimate reality, and the religious significance of general features of the cosmos (e.g., the laws of nature, the emergence of consciousness) and of historical events (e.g., the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake, the Holocaust). Philosophy of religion also includes the investigation and assessment of worldviews (such as secular naturalism) that are alternatives to religious worldviews. Philosophy of religion involves all the main areas of philosophy: metaphysics, epistemology, value theory (including moral theory and applied ethics), philosophy of language, science, history, politics, art, and so on. Section 1 offers an overview of the field and its significance, with subsequent sections covering developments in the field since the mid-twentieth century. These sections address philosophy of religion as practiced primarily (but not exclusively) in departments of philosophy and religious studies that are in the broadly analytic tradition. The entry concludes with highlighting the increasing breadth of the field, as more traditions outside the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) have become the focus of important philosophical work.

- 1. The Field and its Significance

- 2. The Meaning of Religious Beliefs

- 3. Religious Epistemology

- 4. Religion and Science

- 5. Philosophical Reflection on Theism and Its Alternatives

- 6. Religious Pluralism

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. The Field and its Significance

Ideally, a guide to the nature and history of philosophy of religion would begin with an analysis or definition of religion. Unfortunately, there is no current consensus on a precise identification of the necessary and sufficient conditions of what counts as a religion. We therefore currently lack a decisive criterion that would enable clear rulings whether some movements should count as religions (e.g., Scientology or Cargo cults of the Pacific islands). But while consensus in precise details is elusive, the following general depiction of what counts as a religion may be helpful:

A religion involves a communal, transmittable body of teachings and prescribed practices about an ultimate, sacred reality or state of being that calls for reverence or awe, a body which guides its practitioners into what it describes as a saving, illuminating or emancipatory relationship to this reality through a personally transformative life of prayer, ritualized meditation, and/or moral practices like repentance and personal regeneration. [This is a slightly modified definition of the one for “Religion” in the Dictionary of Philosophy of Religion, Taliaferro & Marty 2010: 196–197; 2018, 240.]

This definition does not involve some obvious shortcomings such as only counting a tradition as religious if it involves belief in God or gods, as some recognized religions such as Buddhism (in its main forms) does not involve a belief in God or gods. Although controversial, the definition provides some reason for thinking Scientology and the Cargo cults are proto-religious insofar as these movements do not have a robust communal, transmittable body of teachings and meet the other conditions for being a religion. (So, while both examples are not decisively ruled out as religions, it is perhaps understandable that in Germany, Scientology is labeled a “sect”, whereas in France it is classified as “a cult”.) For a discussion of other definitions of religion, see Taliaferro 2009, chapter one, and for a recent, different analysis, see Graham Oppy 2018, chapter three. The topic of defining religion is re-engaged below in the section 4, “Religion and Science”. But rather than devoting more space to definitions at the outset, a pragmatic policy will be adopted: for the purpose of this entry, it will be assumed that those traditions that are widely recognized today as religions are, indeed, religions. It will be assumed, then, that religions include (at least) Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and those traditions that are like them. This way of delimiting a domain is sometimes described as employing a definition by examples (an ostensive definition) or making an appeal to a family resemblance between things. It will also be assumed that Greco-Roman views of gods, rituals, the afterlife, the soul, are broadly “religious” or “religiously significant”. Given the pragmatic, open-ended use of the term “religion” the hope is to avoid beginning our inquiry with a procrustean bed.

Given the above, broad perspective of what counts as religion, the roots of what we call philosophy of religion stretch back to the earliest forms of philosophy. From the outset, philosophers in Asia, the Near and Middle East, North Africa, and Europe reflected on the gods or God, duties to the divine, the origin and nature of the cosmos, an afterlife, the nature of happiness and obligations, whether there are sacred duties to family or rulers, and so on. As with each of what would come to be considered sub-fields of philosophy today (like philosophy of science, philosophy of art), philosophers in the Ancient world addressed religiously significant themes (just as they took up reflections on what we call science and art) in the course of their overall practice of philosophy. While from time to time in the Medieval era, some Jewish, Christian, and Islamic philosophers sought to demarcate philosophy from theology or religion, the evident role of philosophy of religion as a distinct field of philosophy does not seem apparent until the mid-twentieth century. A case can be made, however, that there is some hint of the emergence of philosophy of religion in the seventeenth century philosophical movement Cambridge Platonism. Ralph Cudworth (1617–1688), Henry More (1614–1687), and other members of this movement were the first philosophers to practice philosophy in English; they introduced in English many of the terms that are frequently employed in philosophy of religion today, including the term “philosophy of religion”, as well as “theism”, “consciousness”,and “materialism”. The Cambridge Platonists provided the first English versions of the cosmological, ontological, and teleological arguments, reflections on the relationship of faith and reason, and the case for tolerating different religions. While the Cambridge Platonists might have been the first explicit philosophers of religion, for the most part, their contemporaries and successors addressed religion as part of their overall work. There is reason, therefore, to believe that philosophy of religion only gradually emerged as a distinct sub-field of philosophy in the mid-twentieth century. (For an earlier date, see James Collins’ stress on Hume, Kant and Hegel in The Emergence of Philosophy of Religion, 1967.)

Today, philosophy of religion is one of the most vibrant areas of philosophy. Articles in philosophy of religion appear in virtually all the main philosophical journals, while some journals (such as the International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Religious Studies, Sophia, Faith and Philosophy, and others) are dedicated especially to philosophy of religion. Philosophy of religion is in evidence at institutional meetings of philosophers (such as the meetings of the American Philosophical Association and of the Royal Society of Philosophy). There are societies dedicated to the field such as the Society for Philosophy of Religion (USA) and the British Society for Philosophy of Religion and the field is supported by multiple centers such as the Center for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Notre Dame, the Rutgers Center for Philosophy of Religion, the Centre for the Philosophy of Religion at Glasgow University, The John Hick Centre for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Birmingham, and other sites (such as the University of Roehampton and Nottingham University). Oxford University Press published in 2009 The History of Western Philosophy of Religion in five volumes involving over 100 contributors (Oppy & Trakakis 2009), and the Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Religion in five volumes, with over 350 contributors from around the world, is scheduled for publication by 2021. What accounts for this vibrancy? Consider four possible reasons.

First: The religious nature of the world population. Most social research on religion supports the view that the majority of the world’s population is either part of a religion or influenced by religion (see the Pew Research Center online). To engage in philosophy of religion is therefore to engage in a subject that affects actual people, rather than only tangentially touching on matters of present social concern. Perhaps one of the reasons why philosophy of religion is often the first topic in textbook introductions to philosophy is that this is one way to propose to readers that philosophical study can impact what large numbers of people actually think about life and value. The role of philosophy of religion in engaging real life beliefs (and doubts) about religion is perhaps also evidenced by the current popularity of books for and against theism in the UK and USA.

One other aspect of religious populations that may motivate philosophy of religion is that philosophy is a tool that may be used when persons compare different religious traditions. Philosophy of religion can play an important role in helping persons understand and evaluate different religious traditions and their alternatives.

Second: Philosophy of religion as a field may be popular because of the overlapping interests found in both religious and philosophical traditions. Both religious and philosophical thinking raise many of the same, fascinating questions and possibilities about the nature of reality, the limits of reason, the meaning of life, and so on. Are there good reasons for believing in God? What is good and evil? What is the nature and scope of human knowledge? In Hinduism; A Contemporary Philosophical Investigation (2018), Shyam Ranganathan argues that in Asian thought philosophy and religion are almost inseparable such that interest in the one supports an interest in the other.

Third, studying the history of philosophy provides ample reasons to have some expertise in philosophy of religion. In the West, the majority of ancient, medieval, and modern philosophers philosophically reflected on matters of religious significance. Among these modern philosophers, it would be impossible to comprehensively engage their work without looking at their philosophical work on religious beliefs: René Descartes (1596–1650), Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), Anne Conway (1631–1679), Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673), Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), John Locke (1632–1704), George Berkeley (1685–1753), David Hume (1711–1776), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), and G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831) (the list is partial). And in the twentieth century, one should make note of the important philosophical work by Continental philosophers on matters of religious significance: Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980), Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986), Albert Camus (1913–1960), Gabriel Marcel (1889–1973), Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929), Martin Buber (1878–1956), Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995), Simone Weil (1909–1943) and, more recently Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), Michel Foucault (1926–1984), and Luce Irigary (1930–). Evidence of philosophers taking religious matters seriously can also be found in cases of when thinkers who would not (normally) be classified as philosophers of religion have addressed religion, including A.N. Whitehead (1861–1947), Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), G.E. Moore (1873–1958), John Rawls (1921–2002), Bernard Williams (1929–2003), Hilary Putnam (1926–2016), Derek Parfit (1942–2017), Thomas Nagel (1937–), Jürgen Habermas (1929–), and others.

In Chinese and Indian philosophy there is an even greater challenge than in the West to distinguish important philosophical and religious sources of philosophy of religion. It would be difficult to classify Nagarjuna (150–250 CE) or Adi Shankara (788–820 CE) as exclusively philosophical or religious thinkers. Their work seems as equally important philosophically as it is religiously (see Ranganathan 2018).

Fourth, a comprehensive study of theology or religious studies also provides good reasons to have expertise in philosophy of religion. As just observed, Asian philosophy and religious thought are intertwined and so the questions engaged in philosophy of religion seem relevant: what is space and time? Are there many things or one reality? Might our empirically observable world be an illusion? Could the world be governed by Karma? Is reincarnation possible? In terms of the West, there is reason to think that even the sacred texts of the Abrahamic faith involve strong philosophical elements: In Judaism, Job is perhaps the most explicitly philosophical text in the Hebrew Bible. The wisdom tradition of each Abrahamic faith may reflect broader philosophical ways of thinking; the Christian New Testament seems to include or address Platonic themes (the Logos, the soul and body relationship). Much of Islamic thought includes critical reflection on Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, as well as independent philosophical work.

Let us now turn to the way philosophers have approached the meaning of religious beliefs.

...

4. The Supremacy of the Spiritual Powers

The Supremacy of the Spiritual

Not by might, nor by power, but by my spirit, saith the Lord of hosts.—Zechariah 4:6.

The Supremacy of the Spiritual Powers - Google Search

__________________________________

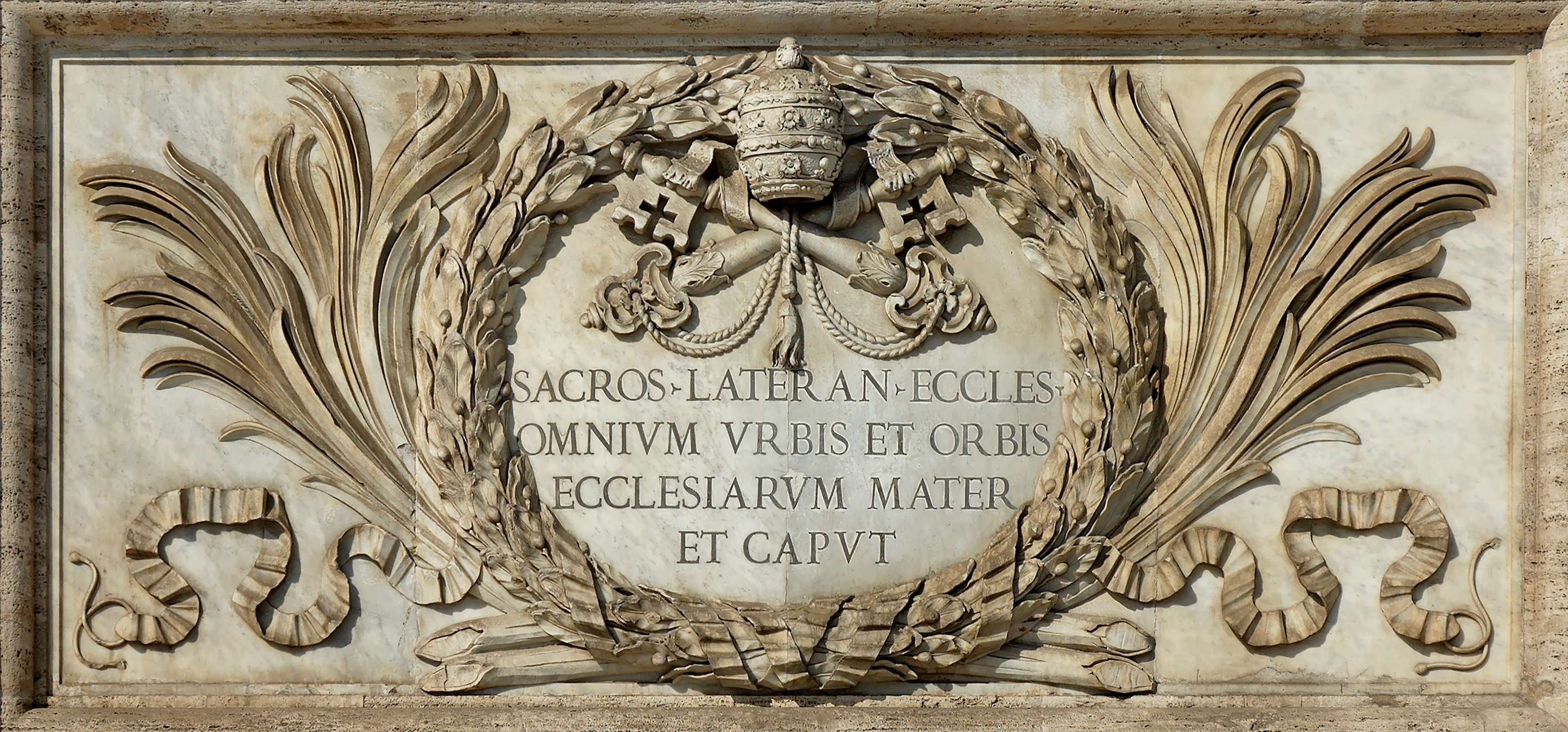

5. The Papal Supremacy

Papal Supremacy:

Papal supremacy is the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church that the Pope, by reason of his office as Vicar of Christ and as the visible foundation and source of unity, and as pastor of the entire Christian Church, has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise ...

The Development of Papal Supremacy

M.N.: this is very good, informative article, read it in its entirety.

Pope Gregory I (c. 540–604) who established medieval themes in the church, in a painting by Carlo Saraceni, c. 1610, Rome.

_______________________________________________

6. Other Related Searches

The moral authority of Pope and its nature

Church Powers as State Powers

Byzantinism and the concept of the Third Rome

The Christian Churches: conflicts and unities

The concepts and the practices of the Stately and the Divine in the Roman Catholic Church and the Russian Orthodox Church

The Stately and the Divine in Christianity, Judaism, and Buddhism

The Nature of Human Powers

The Nature of State Powers

State Powers as Oppression and Coercion

The Nature of Divine Powers

Divine Powers as the powers of Insight and Epiphanies

The Nature of Conflict between Human and Divine Powers

The nature of Spirit, Hegel on evolution of Spirit

Nature of Soul

Spirit and Soul

Collective mind, collective spirit, and collective soul, and their roles in the regulation of social-political processes

Group and Leader, Individual Spirit vs. Collective Spirit

Institutions as Social Structure

Individual Institutional Leadership

Guiding Institutional Spirit

On the need to love, accept and incorporate your opponents as one of the cornerstones of Christian Teaching

Devil as the Fallen Angel

The Dichotomy and the Continuum of Sin and Virtue

Good and Evil

The Angelic and the Satanic

The Devil Worshiping and its place in the Religious Thought

The Unity Of the Angelic and the Satanic Powers

The legal perspectives on the Satanic rituals and Devil Worshiping

Devil worshiping practices in the Middle East, Yasidis

The nature of human beliefs as opposed to Scientific Knowledge

Scientific Knowledge as the Belief System

Kuhn on the nature and development of the Paradigms

The ultimate unity of Belief and Knowledge

Conclusions: Why the Spiritual and the Priestly powers have primacy over the Earthly powers and the powers of Force

The Nature of the Divine

Origins of Christianity, Judaism, other religions, and Religion in general

______________________________________________

Post Link - 12:39 AM 1/4/2020

Links und References

_________________________________________________

.jpg)

A boy carries a portrait of Gen. Qassem Soleimani in Tehran, Iran, Jan. 3, 2020. Iran has vowed “harsh retaliation” for the assassination of Soleimani. Vahid Salemi | AP

A boy carries a portrait of Gen. Qassem Soleimani in Tehran, Iran, Jan. 3, 2020. Iran has vowed “harsh retaliation” for the assassination of Soleimani. Vahid Salemi | AP

Pope Francis greets Cardinal Angelo Sodano, now dean emeritus of the College of Cardinals, during his annual audience to give Christmas greetings to members of the Roman Curia at the Vatican Dec. 21, 2019. The pope has accepted the resignation of Cardinal Sodano as dean of the College of Cardinals. The pope changed the norms to specify that the dean would be elected to a five-year term, renewable once, instead of being elected for life or until choosing to resign. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Pope Francis greets Cardinal Angelo Sodano, now dean emeritus of the College of Cardinals, during his annual audience to give Christmas greetings to members of the Roman Curia at the Vatican Dec. 21, 2019. The pope has accepted the resignation of Cardinal Sodano as dean of the College of Cardinals. The pope changed the norms to specify that the dean would be elected to a five-year term, renewable once, instead of being elected for life or until choosing to resign. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

It's that time of year when we all give thanks and look back on the year, and here at AlterNet we give thanks to you. All of us are honored by your readership and support. We hope you and your family enjoy a joyful holiday season.

It's that time of year when we all give thanks and look back on the year, and here at AlterNet we give thanks to you. All of us are honored by your readership and support. We hope you and your family enjoy a joyful holiday season.

Comments

Post a Comment