Amerithrax: Unresolved! | 2001 Anthrax Mailings and the Amerithrax Investigation - REVISITED: Book Review

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

"The FBI’s investigation into the 2001 mailings, labeled Amerithrax, remains a salient fixture on the post-9/11 landscape. Amerithrax was one of the largest and most complex in American history. It involved more than 10,000 witness interviews worldwide, 80 separate searches, and the recovery of more than 6,000 items of potential evidence, including 5,730 environmental samples from 60 site locations. The lessons of the investigation are crucial to understanding not only the U.S. government’s response to the first deadly bioterror attack on American soil, but also the role scientific evidence does — and does not — play in efforts to attribute bioterror attacks to an individual or group. Today, notwithstanding significant advances in bioforensics, the debates that continue to surround the Amerithrax investigation findings, the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons attacks, or the Russian involvement in the Skripal poisonings are all examples of the doubts confronting even the most earnest attribution efforts."

...

"With the suicide of Bruce Ivins, the Amerithrax investigation closed and the scientific methods developed in the case were never tested or proven in court. Questions about the viability of the scientific findings remained. In response, the FBI requested the National Academies of Science’s National Research Council independently review the bureau’s scientific work as it related to Amerithrax.

Highlighting the limitations of microbial forensics, the council concluded “it is not possible to reach a definitive conclusion about the origins of the B. anthracis in the mailings based on the available scientific evidence alone.” Although the results of the FBI’s microbial forensics were consistent with RMR-1029 or its descendants as the source material for the anthrax mailings, the science itself was not definitive and was insufficient to cast the shadow of guilt on Ivins."

Revisiting the 2001 Anthrax Mailings and the Amerithrax Investigation

-

"Buried in the McClatchy article is an admission from a source close to the investigation that seems to shed some light on why the FBI continues to insist that Ivins was the sole attacker, even going so far as to concoct an after-the-fact “forensic psychiatric profile” in an effort to bolster their case:

“If they ever had any doubts, once he committed suicide, they had to unite,” this person said. “Otherwise, you’ve driven an innocent man to suicide. And that’s a terrible thing.”

Yes, driving a man to suicide is a terrible thing. But is it any less terrible to continue to insist on the guilt of a man who cannot conclusively be proven to have carried out these horrendous attacks ten years ago?"

McClatchy Points Out Key FBI Failure in Amerithrax Investigation

-

Amerithrax

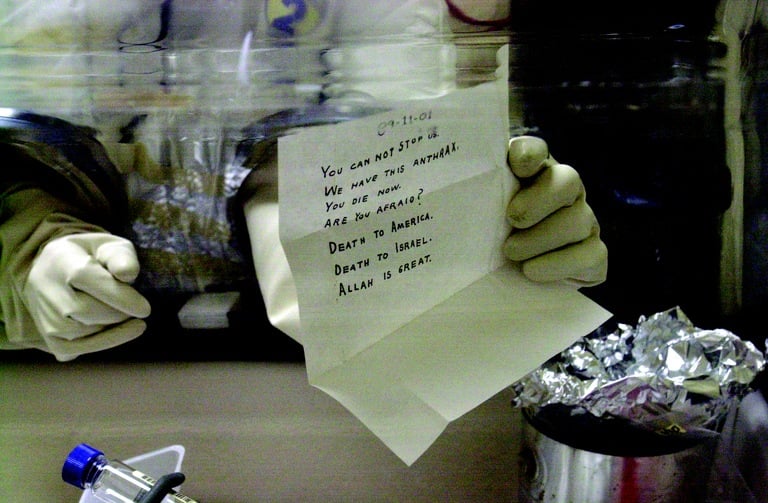

In the immediate aftermath of September 11th, a letter-writing campaign took aim at the media and political figures. These letters, which started being mailed just a week after 9/11, contained lethal doses of anthrax. When the damage was calculated, dozens were exposed, seventeen were infected, and five were dead. Years later, questions still linger over the case dubbed "Amerithrax."

In the immediate aftermath of September 11th, a letter-writing campaign took aim at the media and political figures. These letters, which started being mailed just a week after 9/11, contained lethal doses of anthrax. When the damage was calculated, dozens were exposed, seventeen were infected, and five were dead. Years later, questions still linger over the case dubbed "Amerithrax."

-

Death in the Air: Revisiting the 2001 Anthrax Mailings and the ...

War on the Rocks-2 hours ago

Scott Decker, Recounting the Anthrax Attacks: Terror, the Amerithrax Task ... The FBI's investigation into the 2001 mailings, labeled Amerithrax, ...

FBI, Laying Out Evidence, Closes Anthrax Case

New York Times-Feb 19, 2010

WASHINGTON — More than eight years after anthrax-laced letters killed ... details to its case that the 2001 attacks were carried out by Bruce E. Ivins, ... A 92-page report, which concludes what by many measures is the largest investigation in F.B.I. history, laid ... Documents: Amerithrax Investigation Report ...

FBI investigation of 2001 anthrax attacks concluded; US releases details

Highly Cited-Washington Post-Feb 19, 2010

Highly Cited-Washington Post-Feb 19, 2010

A Look at Mail Attacks in the US

Voice of America-Oct 29, 2018

One of the the most prominent mail attacks occurred in 2001, days ... in the anthrax attacks, also known as Amerithrax from its FBI investigation ...

A history of violence: Letter bomb campaigns in the US

Sky News-Oct 25, 2018

By Aubrey Allegretti, news reporter. The US has seen a number of incidents where explosive or toxic devices have been sent to public figures ...

The Anthrax Letters That Terrorized a Nation Are Now ...

Smithsonian-Sep 12, 2016

Now that it was undeniable that terroristic anthrax attacks were underway, ... During the course of a seven-year investigation, a prime suspect ...

Timeline: How The Anthrax Terror Unfolded

NPR-Feb 15, 2011

11, 2001, anonymous letters laced with deadly anthrax spores began ... Service formally conclude their investigations of the anthrax mailings.

2001 Anthrax Attacks Fast Facts

CNN-Aug 23, 2013

... Here's a look at the 2001 anthrax attacks, also referred to as Amerithrax. ... Anthrax has been blamed for several plagues over the ages that ...

Inquiry in Anthrax Mailings Had Gaps, Report Says

New York Times-Dec 19, 2014

... work on the anthrax mailings of 2001 has identified major gaps in genetic ... independent review of the Amerithrax investigation to ensure we ...

Detrick lab addresses flaws in FBI's Amerithrax investigation

International-Frederick News Post-Dec 19, 2014

International-Frederick News Post-Dec 19, 2014

Microbial forensics used to solve the case of the 2001 anthrax attacks

Science Daily (press release)-Mar 7, 2011

"This paper and the Amerithrax investigation really marked the beginning of a new approach for the science we call forensic genomics," says ...

Oxford Woman, 94, An Unlikely Victim Of Anthrax Attacks

Hartford Courant-Apr 14, 2014

Oxford Woman, 94, An Unlikely Victim Of Anthrax Attacks .... new team on the investigation of the 2001 anthrax attacks, dubbed Amerithrax.

Former FBI Agent Sues, Claiming Retaliation Over Misgivings in ...

New York Times-Apr 8, 2015

Now, a former senior F.B.I. agent who ran the anthrax investigation for ... 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, causing a huge and costly disruption in the ...

After Amerithrax: Biodefense in a post-9/11 America

The Biological SCENE-Sep 25, 2016

For comparison, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was called on more ... Then, following the 2001 anthrax attacks, that multiagency planning ...

From the Vault: Local scientist's hatred for UC sorority led to national ...

WCPO-Aug 3, 2017

After the anthrax attacks in 2001, however, Ivins' program ... to go on a date with him, documents from the Amerithrax investigation said.

Revisiting Mueller and the anthrax case

Boston Globe-Jun 14, 2011

... explores the anthrax letter attacks of 2001, documents that Mueller exerted far-reaching control over the FBI-led “Amerithrax'' investigation.

Comey, Mueller bungled big anthrax case together

OCRegister-May 22, 2017

They botched the investigation of the 2001 anthrax letter attacks that took five lives and infected 17 other people, shut down the U.S. Capitol ...

Poor methods weakened FBI investigation of 2001 anthrax attacks ...

Science AAAS-Dec 22, 2014

FBI's investigation of the 2001 anthrax letter attacks that killed five .... about the accuracy of their scientific findings in the Amerithrax case are ...

How anthrax sleuths cracked the case by decoding genetic 'fingerprints'

Washington Post-Apr 16, 2011

The researchers had been swept into Amerithrax, the massive federal investigationinto the 2001 anthrax mailings, and they yearned for a ...

New Evidence Adds Doubt to FBI's Case Against Anthrax Suspect

ProPublica-Oct 10, 2011

New Evidence Adds Doubt to FBI's Case Against Anthrax Suspect ... WASHINGTON – Months after the anthrax mailings that terrorized the nation in 2001, and long .... final report on the anthrax investigation, called Amerithrax.

Public health leaders cite lessons of 2001 anthrax attacks

CIDRAP-Sep 1, 2011

Public health leaders cite lessons of 2001 anthrax attacks ... plus a chronology of key events and a summary of the anthrax investigation.

Anthrax Redux: Did the Feds Nab the Wrong Guy?

Wired News-Mar 24, 2011

Even agent Edward Montooth, who ran the FBI's hunt for the anthrax killer, .... Investigating the 2001 anthrax attacks required an unprecedented ...

-

But newly available documents and the accounts of Ivins’ former colleagues shed fresh light on the evidence and, while they don't exonerate Ivins, are at odds with some of the science and circumstantial evidence that the government said would have convicted him of capital crimes. While prosecutors continue to vehemently defend their case, even some of the government’s science consultants wonder whether the real killer is still at large.

But newly available documents and the accounts of Ivins’ former colleagues shed fresh light on the evidence and, while they don't exonerate Ivins, are at odds with some of the science and circumstantial evidence that the government said would have convicted him of capital crimes. While prosecutors continue to vehemently defend their case, even some of the government’s science consultants wonder whether the real killer is still at large.

The significance of B. subtilis being present in some of the attack material cannot be overstated, especially when the FBI admits that they were able to obtain a unique DNA fingerprint of the strain that was present. As I wrote last year, I suspect that Defense Department personnel at either Dugway or Batelle cultured the material used in the attacks and noted personnel there have worked with both anthrax and B. sublitlis:

The significance of B. subtilis being present in some of the attack material cannot be overstated, especially when the FBI admits that they were able to obtain a unique DNA fingerprint of the strain that was present. As I wrote last year, I suspect that Defense Department personnel at either Dugway or Batelle cultured the material used in the attacks and noted personnel there have worked with both anthrax and B. sublitlis:

-

This story is a joint project with ProPublica, PBS Frontline and McClatchy. The story will air on Frontline on Oct. 11. Check local listings.

WASHINGTON – Months after the anthrax mailings that terrorized the nation in 2001, and long before he became the prime suspect, Army biologist Bruce Ivins sent his superiors an email offering to help scientists trace the killer.

Already, an FBI science consultant had concluded that the attack powder was made with a rare strain of anthrax known as Ames that's used in research laboratories worldwide.

In his email, Ivins volunteered to help take things further. He said he had several variants of the Ames strain that could be tested in “ongoing genetic studies" aimed at tracing the origins of the powder that had killed five people. He mentioned several cultures by name, including a batch made mostly of Ames anthrax that had been grown for him at an Army base in Dugway, Utah.

Seven years later, as federal investigators prepared to charge him with the same crimes he'd offered to help solve, Ivins, who was 62, committed suicide. At a news conference, prosecutors voiced confidence that Ivins would have been found guilty. They said years of cutting-edge DNA analysis had borne fruit, proving that his spores were “effectively the murder weapon.”

To many of Ivins’ former colleagues at the germ research center in Fort Detrick, Md., where they worked, his invitation to test the Dugway material and other spores in his inventory is among numerous indications that the FBI got the wrong man.

What kind of murderer, they wonder, would ask the cops to test his own gun for ballistics?

To prosecutors, who later branded Ivins the killer in a lengthy report on the investigation, his solicitous email is trumped by a long chain of evidence, much of it circumstantial, that they say would have convinced a jury that he prepared the lethal powder right under the noses of some of the nation’s foremost bio-defense scientists.

PBS' Frontline, McClatchy and ProPublica have taken an in-depth look at the case against Ivins, conducting dozens of interviews and reviewing thousands of pages of FBI files. Much of the case remains unchallenged, notably the finding that the anthrax letters were mailed from Princeton, N.J., just steps from an office of the college sorority that Ivins was obsessed with for much of his adult life.

But newly available documents and the accounts of Ivins’ former colleagues shed fresh light on the evidence and, while they don't exonerate Ivins, are at odds with some of the science and circumstantial evidence that the government said would have convicted him of capital crimes. While prosecutors continue to vehemently defend their case, even some of the government’s science consultants wonder whether the real killer is still at large.

But newly available documents and the accounts of Ivins’ former colleagues shed fresh light on the evidence and, while they don't exonerate Ivins, are at odds with some of the science and circumstantial evidence that the government said would have convicted him of capital crimes. While prosecutors continue to vehemently defend their case, even some of the government’s science consultants wonder whether the real killer is still at large.

Prosecutors have said Ivins tried to hide his guilt by submitting a set of false samples of his Dugway spores in April 2002. Tests on those samples didn’t display the telltale genetic variants later found in the attack powder and in sampling from Ivins’ Dugway flask.

Yet records discovered by Frontline, McClatchy and ProPublica reveal publicly for the first time that Ivins made available at least three other samples that the investigation ultimately found to contain the crucial variants, including one after he allegedly tried to deceive investigators with the April submission.

Paul Kemp, who was Ivins’ lawyer, said the government never told him about two of the samples, a discovery he called “incredible." The fact that the FBI had multiple samples of Ivins’ spores that genetically matched anthrax in the letters, Kemp said, debunks the charge that the biologist was trying to cover his tracks.

Asked about the sample submissions, as well as other inconsistencies and unanswered questions in the Justice Department’s case, lead federal prosecutor Rachel Lieber said she was confident that a jury would have convicted Ivins.

“You can get into the weeds, and you can take little shots of each of these aspects of our vast, you know, mosaic of evidence against Dr. Ivins,” she said in an interview. But in a trial, she said, prosecutors would have urged jurors to see the big picture.

“And, ladies and gentlemen, the big picture is, you have, you know, brick upon brick upon brick upon brick upon brick of a wall of evidence that demonstrates that Dr. Ivins was guilty of this offense.”

Scientists who worked on the FBI’s case do not all share her certainty. Claire Fraser-Liggett, a genetics consultant whose work provided some of the most important evidence linking Ivins to the attack powder, said she would have voted to acquit.

“I don’t know how it would have been possible to convict him," said Fraser-Liggett, the director of the University of Maryland’s Institute for Genome Sciences. “Should he have had access to a potential bio-weapon, given everything that’s come to light? I’d say no. Was he just totally off the wall, from everything I’ve seen and read? I’d say yes.

“But that doesn’t mean someone is a cold-blooded killer."

The Justice Department formally closed the anthrax case last year. In identifying Ivins as the perpetrator, prosecutors pointed to his deceptions, his shifting explanations, his obsessions with the sorority and a former lab technician, his penchant for taking long drives to mail letters under pseudonyms from distant post offices and, after he fell into drinking and depression with the FBI closing in, his violent threats during group therapy sessions. An FBI search of his home before he died turned up a cache of guns and ammunition.

Most of all, though, prosecutors cited the genetics tests as conclusive evidence that Ivins’ Dugway spores were the parent material to the powder.

Yet, the FBI never could prove that Ivins manufactured the dry powder from the type of wet anthrax suspensions used at Fort Detrick. It couldn’t prove that he scrawled letters mimicking the hateful rhetoric of Islamic terrorists. And it couldn’t prove that he twice slipped away to Princeton to mail the letters to news media outlets and two U.S. senators; it could prove only that he had an opportunity to do so undetected.

The $100 million investigation did establish that circumstantial evidence could mislead even investigators armed with unlimited resources.

Before focusing on Ivins, the FBI spent years building a case against another former Army scientist. Steven Hatfill had commissioned a study on the effectiveness of a mailed anthrax attack and had taken ciprofloxacin, a powerful antibiotic used to treat or prevent anthrax, around the dates of the mailings. Then-Attorney General John Ashcroft called Hatfill a “person of interest,” and the government eventually paid him a $5.8 million settlement after mistakenly targeting him.

Ivins’ colleagues and some of the experts who worked on the case wonder: Could the FBI have made the same blunder twice?

Did Ivins have a motive?

Growing up in Ohio, the young Bruce Ivins showed an early knack for music and science. But his home life, described as “strange and traumatic” in a damning psychological report released after his death, left scars that wouldn’t go away.

The report, written by a longtime FBI consultant and other evaluators with court-approved access to Ivins’ psychiatric records, said Ivins was physically abused by a domineering and violent mother and mocked by his father. Ivins developed “the deeply felt sense that he had not been wanted,” the authors found, and he learned to cope by hiding his feelings and avoiding confrontation with others.

Ivins attended the University of Cincinnati, staying there until he earned a doctoral degree in microbiology. In his sophomore year, prosecutors say, the socially awkward Ivins had a chance encounter that influenced his life: A fellow student who belonged to the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority spurned him.

For more than 40 years, even as a married man, Ivins was obsessed with KKG, a fixation that he later admitted drove him to multiple crimes. Twice he broke into chapters, once climbing through a window and stealing the sorority’s secret code book.

After taking a research job at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ivins discovered that a doctoral student, Nancy Haigwood, was a KKG alumna, and he tried to strike up a friendship. When she kept him at a distance, Ivins turned stalker, swiping her lab book and vandalizing her fiance’s car and the fence outside her home. Two decades later, when Haigwood received an FBI appeal for scientists nationwide to help find the anthrax mailer, she instantly thought of Ivins and phoned the FBI. Investigators didn’t home in on him for years.

When they did, the mailbox in Princeton, which also was near the home of a former Fort Detrick researcher whom Ivins disliked, loomed large.

“This mailbox wasn’t a random mailbox,” said Edward Montooth, a recently retired FBI agent who ran the inquiry. “There was significance to it for multiple reasons. And when we spoke to some of the behavioral science folks, they explained to us that everything is done for a reason with the perpetrator. And you may never understand it because you don’t think the same way.”

Ivins was a complicated, eccentric man. Friends knew him as a practical jokester who juggled beanbags while riding a unicycle, played the organ in church on Sundays and spiced office parties with comical limericks. William Hirt, who befriended Ivins in grad school and was the best man at his wedding, described him as “a very probing, spiritual fellow that wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

Ivins gained self-esteem and status in his job as an anthrax researcher at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Md.

Even so, his fixations wouldn’t quit.

He became so obsessed with two of his lab technicians that he sent one of them, Mara Linscott, hundreds of email messages after she left to attend medical school in Buffalo, N.Y. Ivins drove to her home to leave a wedding gift on her doorstep. When she left, he wrote a friend, “it was crushing,” and called her “my confidante on everything, my therapist and friend.”

Later, after snooping on email messages in which the two technicians discussed him, Ivins told a therapist that he’d schemed to poison Linscott but aborted the plan at the last minute.

USAMRIID was once a secret germ factory for the Pentagon, but the institute’s assignment shifted to vaccines and countermeasures after the United States and Soviet Union signed an international treaty banning offensive weapons in 1969. A decade later, a deadly leak from a secret anthrax-making facility in the Soviet city of Sverdlovsk made it clear that Moscow was cheating and prompted the United States to renew its defensive measures.

Ivins was among the first to be hired in a push for new vaccines.

By the late 1990s, he was one of USAMRIID’s top scientists, but the institute was enmeshed in controversy. Worried that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had made large quantities of anthrax before the 1991 Persian Gulf War, President Bill Clinton had ordered that all military personnel, not just those in war zones, be inoculated with a 1970s-era vaccine. But soldiers complained of ill health from the vaccine, some blaming it for the symptoms called Gulf War Syndrome.

Later, Karl Rove, political adviser to new President George W. Bush, suggested that it was time to stop the vaccinations. Further, a Pentagon directive—although quickly reversed in 2000—had ordered a halt to research on USAMRIID’s multiple anthrax-vaccine projects.

Federal prosecutors say these developments devastated Ivins, who'd devoted more than 20 years to anthrax research that was now under attack.

“Dr. Ivins’ life’s work appeared destined for failure, absent an unexpected event,” said the Justice Department’s final report on the anthrax investigation, called Amerithrax. Told by a supervisor that he might have to work on other germs, prosecutors say Ivins replied: “I am an anthrax researcher. This is what I do.”

Ivins’ former bosses at Fort Detrick call that Justice Department characterization wrong. Ivins had little to do with the existing vaccine; rather, he was working to replace it with a better, second-generation version, they say.

In the summer of 2001, Ivins shouldn't have had any worries about his future, said Gerard Andrews, who was then his boss as the head of USAMRIID’s Bacteriology Division. “I believe the timeline has been distorted by the FBI,” Andrews said. “It’s not accurate.”

Months earlier, Andrews said, the Pentagon had approved a full year’s funding for research on the new vaccine and was mapping out a five-year plan to invest well over $15 million.

Published reports have suggested that Ivins had another motive: greed. He shared patent rights on the new vaccine. If it ever reached the market, after many more years of testing and study, federal rules allowed him to collect up to $150,000 in annual royalties.

If that was his plan, it didn’t go well. After the attacks, Congress approved billions of dollars for bio-defense and awarded an $877.5 million contract to VaxGen Inc. to make the new vaccine but scrapped it when the California firm couldn’t produce the required 25 million doses within two years.

Ivins received modest royalty payments totaling at least $6,000. He told prosecutors he gave most of the money to others who had worked with him on the project, said Kemp, his defense attorney.

Kemp said prosecutors told him privately that they’d dismissed potential financial returns as a motive. That incentive wasn’t cited in the Justice Department’s final report.

Did Ivins have an opportunity?

The relatively lax security precautions in place at U.S. defense labs before the mailings and Sept. 11 terrorist attacks offered many opportunities for a deranged scientist. Prosecutors said Ivins had easy access to all the tools needed to make the attack spores and letters.

Researchers studying dangerous germs work in a “hot suite," a specially designed lab sealed off from the outside world. The air is maintained at “negative pressure” to prevent germs from escaping. Scientists undress and shower before entering and leaving.

Like many of his colleagues at Fort Detrick, Ivins dropped by work at odd hours. In the summer and fall of 2001, his night and weekend time in the hot suite spiked: 11 hours and 15 minutes in August, 31 hours and 28 minutes in September and 16 hours and 13 minutes in October. He'd averaged only a couple of hours in prior months. Swiping a security card each time he entered and left the suite, he created a precise record of his visits. Rules in place at the time allowed him to work alone.

Sometime before the mailings, prosecutors theorize, Ivins withdrew a sample of anthrax from his flask—labeled RMR-1029—and began to grow large quantities of the deadly germ. If so, his choice of strains seemed inconsistent with the FBI’s portrait of him as a cunning killer. Surrounded by a veritable library of germs, they say, Ivins picked the Dugway Ames spores, a culture that was expressly under his control.

Using the Ames strain “pointed right at USAMRIID," said W. Russell Byrne, who preceded Andrews as the chief of the Bacteriology Division and who's among those convinced of Ivins’ innocence. “That was our bug."

Federal prosecutors have declined to provide a specific account of when they think Ivins grew spores for the attacks or how he made a powder. But the steps required are no mystery.

First, he would have had to propagate trillions of anthrax spores for each letter. The bug can be grown on agar plates (a kind of petri dish), in flasks or in a larger vessel known as a fermenter. Lieber, then an assistant U.S. attorney and lead prosecutor, said the hot suite had a fermenter that was big enough to grow enough wet spores for the letters quickly.

To make the amount of powder found in the letters, totaling an estimated 4 to 5 grams, Ivins would have needed 400 to 1,200 agar plates, according to a report by a National Academy of Sciences panelreleased in May. Growing it in a fermenter or a flask would have been less noticeable, requiring between a few quarts and 14 gallons of liquid nutrients.

Next was drying. Simple evaporation can do the job, but it also would expose other scientists in a hot suite. Lieber said the lab had two pieces of equipment that could have worked faster: a lyophilizer, or freeze dryer; and a smaller device called a “Speed Vac.”

Investigators haven’t said whether they think the Sept. 11 attacks prompted Ivins to start making the powder or to accelerate a plan already under way. However, records show that on the weekend after 9/11, Ivins spent more than two hours each night in the hot suite on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

The next afternoon, Monday, Sept. 17, 2001, he took four hours of annual leave but was back at USAMRIID at 7 p.m. Because of their Sept. 18 postmarks, the anthrax-laced letters had to have been dropped sometime between 5 p.m. Monday and Tuesday’s noon pickup at a mailbox at 10 Nassau St. in Princeton.

If Ivins did make the seven-hour round-trip drive from Fort Detrick, he would've had to travel overnight. Investigators said he reported to USAMRIID at 7 a.m. Tuesday for a business trip to Pennsylvania.

Did Ivins have the means?

Colleagues who worked with Ivins in the hot suite and think that he's innocent say he'd never worked with dried anthrax and couldn’t have made it in the lab without spreading contamination.

Andrews, Ivins’ former boss, said Ivins didn’t know how to use the fastest process, the fermenter, which Andrews described as “indefinitely disabled,” with its motor removed. He said the freeze dryer was outside the hot suite, so using it would have exposed unprotected employees to lethal spores.

Without a fermenter, it would have taken Ivins “30 to 50 weeks of continuous labor” to brew spores for the letters, said Henry Heine, a former fellow Fort Detrick microbiologist who's now with the University of Florida. Prosecutors and a National Academy of Sciences panel that studied the case said the anthrax could have been grown as quickly as a few days, though they didn't specify a method.

FBI searches years later found no traces of the attack powder in the hot suite, lab and drying equipment.

Fraser-Liggett, the FBI’s genetics consultant, questioned how someone who perhaps had to work “haphazardly, quickly" could have avoided leaving behind tiny pieces of forensically traceable DNA from the attack powder.

Lieber, the Justice Department prosecutor, said the FBI never expected to find useable evidence in the hot suite after the equipment had been cleaned multiple times.

“This notion that someone could have stuck a Q-tip up in there and found, you know, a scrap of ‘1029’ DNA, I think is, with all due respect, it’s inconsistent with the reality of what was actually happening," she said.

Yet, in 2007, six years after the letters were mailed, the FBI carefully searched Ivins’ home and vehicleslooking for, among other things, anthrax spores. None were found.

The first round of anthrax letters went to an eclectic media group: Tom Brokaw, the NBC anchor; the tabloid newspaper the New York Post; and the Florida offices of American Media Inc., which publishes the National Enquirer. Just over two weeks later, on Oct. 4, jittery Americans were startled to learn that a Florida photo editor, Robert Stevens, had contracted an extremely rare case of inhalation anthrax.

Stevens died the next day. As prosecutors tell the story, Ivins would hit the road to New Jersey again as early as Oct. 6, carrying letters addressed to the offices of Democratic Sens. Patrick Leahy, the Judiciary Committee chairman from Vermont, and Tom Daschle of South Dakota, the Senate majority leader.

Unlike the brownish, granular, impure anthrax in the earlier letters, this batch was far purer, with tiny particles that floated like a gas, making them more easily inhaled and therefore deadlier.

Just a few hours before those letters were dropped at Nassau Street, investigators had a scientific breakthrough: Paul Keim, an anthrax specialist at Northern Arizona University, verified that the spores in Stevens’ tissues were the Ames strain of anthrax.

“It was a laboratory strain,” Keim recalled later, “and that was very significant to us."

On Oct. 15, an intern in Daschle’s office opened a nondescript envelope with the return address “4th Grade, Greendale School, Franklin Park, NJ 08852." A white powder uncoiled from the rip, eventually swirling hundreds of feet through the Hart Senate Office Building, where dozens of senators work and hold hearings. It would take months and millions of dollars to fully cleanse the building of spores.

Ill-prepared to investigate America’s first anthrax attack, the FBI didn't have a properly equipped lab to handle the evidence, so the Daschle letter and remaining powder were taken to Fort Detrick.

Among those immediately enlisted to examine the attack powder: Bruce Ivins.

The FBI would turn to Ivins time and again in the months and years ahead. At this early moment, he examined the Daschle spores and logged his observations with scientific exactitude. The quality, he determined, suggested “professional manufacturing techniques.”

“It is an extremely pure preparation, and an extremely high concentration," Ivins wrote on Oct. 18, 2001. “These are not 'garage' spores."

Read the whole story

· · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

The case went quiet over the next few months, as investigators continued trying to piece things together. Then, nearly a year after the original letters were mailed, news hit the wire.

On June 25th, 2002, media sources began reported that the FBI had searched the home of Dr. Steven Hatfill, a scientist that worked at the government biodefense lab at Fort Detrick, Maryland.

Steven Hatfill, who was 48 years old at this point in 2002, had been born in Missouri. In 1975, he had enlisted in the US Army, before being discharged in 1977.

After leaving the service, he decided that he wanted to become a doctor, and made the decision to move overseas to Africa, where he began attending numerous schools and working for organizations to bolster his resume. He would grow quite an impressive academic resume, before moving back to the U.S. in the early 1990's, where he began working for the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases - which is a mouthful, more commonly known by its abbreviation, USAMRIID.

This facility, which is located at Fort Detrick - in Maryland - is the only Department of Defense laboratory equipped to study highly hazardous viruses at Biosafety Level 4 within positive pressure personnel suits. Biosafety Level 4 is the highest level of viruses, and includes such infectious agents as small pox, Lassa Fever, Ebola, and others like them.

Dr. Steven Hatfill, who worked as a physician, virologist, biological weapons expert, and overall bio-defense researcher, had been responsible for commissioning a 1999 report, which sought to explore the possibilities of a terrorist anthrax mail attack. This report was later seen as a "blueprint" for the 2001 anthrax attacks, and Dr. Hatfill's name within is what intrigued investigators the most.

Dr. Hatfill had initially come to the attention of investigators when a letter was mailed to a Microsoft office in Reno, Nevada, from the country of Malaysia. Initial reports indicated that the letter tested positive for anthrax, but this would be proven wrong in the following days. However, Dr. Hatfill - whose girlfriend at the time was Malaysian - popped up as an intriguing candidate.

When investigators dug into Dr. Hatfill as a person-of-interest, they discovered that he had taken the anthrax antibiotic Cipro in 2001, shortly before the letters were mailed out. It would later be revealed that he had been prescribed Cipro from his doctor after an unrelated infection, but that did not deter suspicions.

Hatfill's name was brought up in the spring of 2002 as a suspect, and his house was then searched on June 25th. Dr. Hatfill himself agreed to the search, but reports of the search were then leaked to the media, along with his identity.

The FBI began pursuing Dr. Steven Hatfill with every resource at their disposal. His life was lived under the threat of a microscope for the foreseeable future, with the FBI maintaining constant surveillance over a period of years. His phones were tapped, and agents began literally following him around-the-clock.

As a result of his name being leaked to the press as a potential suspect in the anthrax attacks, his reputation was ruined. Shortly thereafter, he lost his security clearance to work at Fort Detrick, and soon thereafter, lost his job as an instructor at Louisiana State University.

His reputation was ruined, and he could not gain employment anywhere.

Despite the damage done to his name and reputation, there was very little reprieve for Dr. Steven Hatfill. He maintained his innocence, but his life changed in August of 2002.

Attorney General John Ashcroft, speaking to the press, announced that Dr. Steven Hatfill was being pursued as a "person of interest" in the investigation into the anthrax outbreak from the year before, officially putting him in the sights of the media. He was now a named suspect in the deadliest bio-weapon attack in American history, which had taken place in the immediate aftermath of September 11.

The next week, outside of his lawyer's office, Dr. Steven Hatfill plead with the media to treat him fairly. He stated, emphatically:

"I am not the anthrax killer."

His lawyer, Victor M. Glasberg, made a similar assertion moments later:

"Steve's life has been devastated by a drumbeat of innuendo, implication, and speculation. We have a frightening public attack on an individual who, guilty or not, should not be exposed to this type of public opprobrium based on speculation."

Read the whole story

· · ·

By Jim White

FireDogLake | April 21, 2011

FireDogLake | April 21, 2011

In an article published Wednesday evening on their website, McClatchy points out yet another failing in the FBI’s Amerithrax investigation of the 2001 anthrax attacks that killed five people. The article focuses on the fact that the FBI was able to get a clear genetic fingerprint of a bacterial contaminant that was found in the attack material mailed to the New York Post and to Tom Brokaw (but not to either Senator Daschle or Senator Leahy). This contaminant, Bacillus subtilis, is used in some cases by weapons laboratories as an anthrax simulant, because its behavior in culture and in drying the spores is very similar to Bacillus anthracis but it is easier to handle because it is not pathogenic. I covered the FBI’s failure to link this B. subtilis contaminant to Ivins in this diary in February of 2010.

A key finding in the McClatchy article comes from an FBI memo they obtained:

One senior FBI official wrote in March 2007, in a recently declassified memo, that the potential clue “may be the most resolving signature found in the evidence to date.”

The genetic fingerprint of the B. subtilis contaminant, in other words, was a very definitive clue that needed to be traced to the culprit. The problem, as McClatchy points out, is that the FBI never got a match to materials from Ivins or from anyone else:

Yet once FBI agents concluded that the likely culprit was Bruce Ivins — a mentally troubled, but widely regarded Army microbiologist — they stopped looking for the contaminant, after testing only a few work spaces of the scores of researchers using the anthrax strain found in the letters. They quit searching, despite finding no traces of the substance in hundreds of environmental samples from Ivins’ lab, office, car and home.

LSU anthrax researcher Martin Hugh-Jones makes the key point in his discussion with McClatchy, in response to being informed the government tested thousands of samples for a match to the B. subtilis contaminant, “But were they thousands of the right samples?”

Even though Ivins can’t be linked to the particular B. subtilis strain used, there is a documented case of B. subtilis being used as a B. anthracis simulant at another facility where we already know that much of the material that went into RMR-1029 was produced. Recall from this diary that I analyzed the available information about the amount of B. anthracis used in the attacks and found it highly unlikely that Ivins could have cultured the large amount of spores used in the attacks with the equipment and time he had available. Much of the material in RMR-1029 was produced at Dugway.

On December 13, 2001, Judith Miller published an article in the New York Times, where she disclosed that “government officials have acknowledged that Army scientists in recent years have made anthrax in a powdered form that could be used as a weapon.” She further pointed out that this work occurred at Dugway in 1998. It should be noted that the anthrax produced at Dugway for Ivins that went into RMR-1029 was cultured in 1997.

The Miller article then goes on to quote scientist William C. Patrick on how he coached scientists at Dugway in drying a pound of highly purified anthrax spores in 1998. Miller quotes a Dugway spokesperson as saying a strain different from Ames (the parent of RMR-1029) was used in the drying experiments. Note that a pound of spores is enough dried spores to produce hundreds of letters with the one to two grams of dried spores thought to be in each letter. But in a further bit from the Dugway spokesperson, we have this:

She said Dugway did make one- pound quantities of Bacillus subtilis, a benign germ sometimes used to simulate anthrax.

We know that the key anthrax work at Dugway and Batelle was carried out by the Defense Intelligence Agency. I find it highly unlikely that this agency would be completely forthcoming with the FBI in sharing samples of all of the B. anthracis or B. subtilis strains in its collection, so Hugh-Jones was right to question whether the FBI tested the right samples for a match to the key B. subtilis contaminant. The fact that all of Ivins’ materials were available to the FBI, and that the FBI was able to carry out extensive environmental sampling (albeit several years after the preparation of the attack materials) where Ivins worked and lived comes very close to excluding Ivins as a suspect since the contaminant was not found in association with him.

Buried in the McClatchy article is an admission from a source close to the investigation that seems to shed some light on why the FBI continues to insist that Ivins was the sole attacker, even going so far as to concoct an after-the-fact “forensic psychiatric profile” in an effort to bolster their case:

“If they ever had any doubts, once he committed suicide, they had to unite,” this person said. “Otherwise, you’ve driven an innocent man to suicide. And that’s a terrible thing.”

Yes, driving a man to suicide is a terrible thing. But is it any less terrible to continue to insist on the guilt of a man who cannot conclusively be proven to have carried out these horrendous attacks ten years ago?

<a href="http://my.firedoglake.com/jimwhite/2011/04/21/mcclatchy-points-out-key-fbi-failure-in-amerithrax-investigation/" rel="nofollow">http://my.firedoglake.com/jimwhite/2011/04/21/mcclatchy-points-out-key-fbi-failure-in-amerithrax-investigation/</a>

Read the whole story

· · · · ·

Next Page of Stories

Loading...

Page 2

Scott Decker, Recounting the Anthrax Attacks: Terror, the Amerithrax Task Force, and the Evolution of Forensics in the FBI (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

Time may have diminished the memory of the 2001 anthrax attacks and the sense of urgency surrounding the efforts to identify the attacker. The attacks, which involved mailings of five anthrax-laced letters to prominent senators and media outlets, killed five individuals and made 17 others ill. The anthrax mailings played a profound role in raising concerns over possible terrorist use of biological agents in attacks against the homeland. As a result of the anthrax scare, Americans’ perceptions of terrorism came to include an existential fear of biological terrorism (aka “bio-doom”). Though this sense of dread has since diminished in the absence of another biological attack, it persists today because of the recent revolution in biotechnology: a revolution capable of resulting in enormous benefit for humanity as well as catastrophic dangers.

These concerns have fueled enormous growth in federal government spending on biodefense measures, and a cottage industry has arisen to lobby for further resources to combat the bioterror threat. Investments in biodefense have ranged from exponential spending increases and the expansion in the numbers of Bio-Safety Level 3 and 4 laboratories nationwide to the passage of the Bioshield Actin 2004 and the creation of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and Federal Select Agent and Biowatch programs. However, as time passed without a biological attack, concerns about bioterror have diminished and biodefense has arguably become passé, its advocates shifting their attention to health security and pandemic preparedness.

The FBI’s investigation into the 2001 mailings, labeled Amerithrax, remains a salient fixture on the post-9/11 landscape. Amerithrax was one of the largest and most complex in American history. It involved more than 10,000 witness interviews worldwide, 80 separate searches, and the recovery of more than 6,000 items of potential evidence, including 5,730 environmental samples from 60 site locations. The lessons of the investigation are crucial to understanding not only the U.S. government’s response to the first deadly bioterror attack on American soil, but also the role scientific evidence does — and does not — play in efforts to attribute bioterror attacks to an individual or group. Today, notwithstanding significant advances in bioforensics, the debates that continue to surround the Amerithrax investigation findings, the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons attacks, or the Russian involvement in the Skripal poisonings are all examples of the doubts confronting even the most earnest attribution efforts.

Hurdles Facing Bioterrorism Attribution

The investigation ran from late 2001 through to its eventual closing in February 2010, nearly two years after its principal subject, Dr. Bruce Ivins, committed suicide. The investigation found that Ivins was responsible for mailing the anthrax-laced letters in 2001 based on a combination of factors, including motive, opportunity, history of mental health struggles, access to the anthrax spore source, proximity of the source to the envelopes used to mail the spores, and a consciousness of guilt.

One key lesson of Amerithrax was that the United States lacked the means for accurate attribution of bioterror attacks. Attribution of a biological attack is the result of a process that combines the results of traditional forensics (fingerprints, tool marks, fiber, trace element analysis, etc.), bioforensics (genomic signatures and analytical chemistry), and investigative techniques (interviews, polygraphs, surveillances, telephone taps, etc.), which are particularly relevant in cases involving foreign actors, intelligence methods (human intelligence and signal intelligence collection and analysis).

Bioforensics, as a component of attribution, was born out of the Amerithrax investigation. But bioforensics, also commonly referred to as microbial forensics, is only one element of attribution. Because of the “CSI effect” (i.e., a perception resulting from popular television crime shows that laboratory tests can decisively determine guilt), laboratory tests almost certainly have eclipsed other forms of evidence in their influence over juries. In reality, scientific results take a long time to bear fruit and often are not as unambiguous as portrayed in television fiction.

As the Amerithrax investigation began, microbial forensics was in its infancy, and the capabilities were rudimentary compared to current tools. As Dr. Vahid Majidi, former Assistant Director of the FBI’s WMD Directorate, pointed out in his self-published book on Amerithrax, the goal of the investigation was to meet the legal standards, not necessarily the higher standard of scientific proof. Scientific certainty would have been too time-consuming and expensive. The scientific goal of Amerithrax, to paraphrase Majidi, was the good-enough. Dr. Randy Murch, who was involved in establishing the FBI’s microbial forensics efforts in 1996, stated that science will never get all the way to providing attribution, and that’s the way it will always be. Microbial forensics can exclude some possible perpetrators and include a few.

Thus, for all the progress made in the life sciences since 1996, attribution efforts still have a long way to go. No one size fits all the possible universes of possible threat scenarios. Methods remain largely untested in terms of validation and legal acceptance in federal courts. Having not been tested it the courts, questions remain as to whether the methods would meet the Daubert standard, the rule of evidence governing the admissibility of expert witnesses‘ testimony in federal courts. Given that microbial forensics alone is unable to answer the attribution question, attribution must incorporate all the available tools. Majidi stressed that to assign attribution, it was prudent to look at the information from each element independently and, once all the information had been gathered, to bring together the most diagnostic information to arrive at a conclusion. In the end, any attribution effort will be complex, and the results almost certainly will be controversial.

A Useful Insider Account

Scott Decker’s book on Amerithrax is the first and, so far, only insider account of the science involved in the investigation. Decker served as an FBI special agent, one of very few in the bureau with a PhD in the life sciences. His strong academic background and experience in the FBI’s then-fledgling bioforensics effort ensured his rise to a prominent role in the Amerithrax investigation. In time, Decker became the supervisory special agent overseeing Amerithrax’s Squad 2, which was responsible for the scientific and forensics work of the task force.

Thus, Decker is perhaps one of only a handful of people capable of providing comprehensive insight into the inner workings of Amerithrax’s bioforensics effort. His book likely will be the only one to offer such a detailed and unique perspective into the U.S. government’s response to the first deadly bioterrorism attack on American soil in peacetime.

(A disclaimer: For much of the time Amerithrax was active, I was working as a supervisor in the FBI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate, an entity created after 9/11 to counter the threat from terrorist use of improvised nuclear weapons as well as biological and chemical agents. There I came to know many of the players in Decker’s book, although my role was tangential to what came to be the major thrust of the investigation. I focused on supporting Amerithrax’s effort to identify possible international terrorist involvement in the anthrax mailings. I did work with several of the investigation’s special agents and knew of Decker and his work. I certainly cannot claim any insider insight into the scientific work or the efforts as they centered on Bruce Ivins.)

The book is Decker’s first-person account of his role in the case. This perspective is both the book’s major strength and its major weakness. Decker’s focus was on developing and refining the scientific approach to the investigation, so he deftly weaves a compelling account of the scientific aspects of Amerithrax. At the same time, although he certainly was aware of other aspects of Amerithrax, Decker’s book offers no insight into the efforts to examine possible international terrorist involvement in the mailings, an early concern that continued late into the case. I also take issue with Decker on several minor issues in the book, but these all fall into the category of nitpicking and in no way detract from the import of his work.

The Path to Bruce Ivins: An Inadvertent Discovery

Much of the book explores the groundbreaking genetics work that was crucial to identifying Ivins as the lead person of interest in the case. As Decker aptly describes, the bioforensics work of Amerithrax and its collaborators outside of government led to the development of new scientific capabilities of attribution of biological attacks. Yet the crucial scientific lead came by accident. Relatively early in the investigation, a researcher unintentionally let cultures of the B. anthracis used in the mailings incubate longer than planned. These cultures exhibited several unusual physical characteristics (i.e., morphologies) pointing researchers to possible genetic mutations that could be used as identifying signatures.

Absent this accidental discovery and lacking today’s sequencing power, Amerithrax might have been unable to home in on the unique signatures that led them to the RMR-1029 flask in Ivins’ laboratory. Very early in the investigation, investigators learned that the spores in the letters belonged to the Ames strain of B. anthracis, yet early efforts to identify a unique genetic signature eluded them. The accidental discovery of the unique morphologies pointed to a way forward. By focusing on the genetic mutations responsible for the morphologies, researchers uncovered genetic signatures that linked the letter spores to spores originating from the RMR-1029 flask. Given his research at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Ivins had access to that flask. The envelopes used in the attacks also were sourced to several locations in or relatively near Ivins in Frederick, Maryland. But this scientific evidence did not point to Ivins alone. Others working in the same laboratory had access to the same flask, and Ivins had shared samples of spores from RMR-1029 with researchers at other laboratories.

The investigative focus on Ivins was based on both the science that narrowed the source of the B. anthracis in the mailings to that particular spore flask and on Ivins’ own suspicious behaviors. Decker’s book deftly describes the path that led investigators to RMR-1029. In parallel, he paints a compelling picture of Ivins’ mental health demons. Investigators emphasized Ivins’ “consciousness of guilt,” a term of art describing behavior or actions of a guilty individual. In Ivins’ case, the consciousness of guilt involved his deceit when questioned about several material facts related to the case, destruction of incriminating evidence, his deteriorating mental health, and ultimately his suicide. Supposedly Ivins perpetrated the attacks out of an anxiety that his supervisors planned to end Ivins’ anthrax research and reassign him to work on another pathogen. According to this explanation, Ivins mailed the letters to ensure anthrax research remained a priority at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute. In the end, the weight of the evidence pointing to Ivins, as well as the scientific work that identified RMR-1029 as the parent source of the anthrax spores, compelled the Department of Justice to conclude Ivins was the sole perpetrator of the anthrax letter attacks.

Although many of Ivins’ associates have told me that they cannot believe Ivins would have perpetrated the attacks, Decker makes a strong case for Ivins’ role. His case is supported by the findings of the Expert Behavioral Analysis Panel and the Amerithrax Investigative Report. Still, Ivins’ motive remains a matter of debate. Absent the investigation’s identification of RMR-1029 as the source of the anthrax spores in the letters, one has to wonder whether Ivins’ mental health would have ever become an issue. Ivins’ case highlights the difficulty of attributing biological attacks, particularly the inadequacy of scientific evidence to, on its own, point to a perpetrator.

With the suicide of Bruce Ivins, the Amerithrax investigation closed and the scientific methods developed in the case were never tested or proven in court. Questions about the viability of the scientific findings remained. In response, the FBI requested the National Academies of Science’s National Research Council independently review the bureau’s scientific work as it related to Amerithrax. Highlighting the limitations of microbial forensics, the council concluded “it is not possible to reach a definitive conclusion about the origins of the B. anthracis in the mailings based on the available scientific evidence alone.” Although the results of the FBI’s microbial forensics were consistent with RMR-1029 or its descendants as the source material for the anthrax mailings, the science itself was not definitive and was insufficient to cast the shadow of guilt on Ivins.

How Far Have Attribution Efforts Come?

The ongoing revolution in biotechnology would have had a profound effect on Amerithrax had those capabilities been available back in 2002. If the investigation were to take place today, advances in genetic sequencing likely would mean that the case would not have rested on an accidental discovery of unique morphologies to point to signature mutations. The timeframe for the genomic analysis of Amerithrax’s B. anthracis repository also would have been sped up significantly. Decker marvels at the tremendous advances in bioforensics given the exponential increase in sequencing speed and capacity along with a corresponding decrease in cost that took place during Amerithrax and in its aftermath. Decker stated that in 2002 he estimated that sequencing the 1981 Ames strain of B. anthracis would cost close to $500 million and that it would take six months to find an accurate genomic sequence. Today the cost has fallen to tens of thousands of dollars and the time required to complete the sequencing shortened to weeks rather than months.

However, even with the advances of the biotechnology revolution, it is unlikely that bioforensics today can, on its own, put a smoking gun in the hands of any one individual or group. Absent a claim of responsibility, reliable attribution of attacks — whether for use in a court case or to justify military or diplomatic responses to chemical or biological weapon use overseas — must combine sound science with investigative techniques and/or intelligence sources and methods. A 2018 exercise, CladeX, conducted by the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, demonstrated the critical importance of a claim of responsibility for attribution and highlighted the lack of relevant scientific expertise in American investigative and intelligence agencies.

Given the serious consequences of error, decision-makers almost certainly will set a very high bar for attribution in terms of accuracy, reliability, and credibility. Ambiguities in interpreting scientific findings, as well as the limitations and nuances inherent in intelligence reporting, make it difficult for attribution efforts to meet that high bar. Faulty science combined with incomplete investigative work likely would result in a miscarriage of justice. Likewise, reliance on faulty science in the absence of solid intelligence about chemical or biological weapons use overseas would be disastrous diplomatically and militarily. Attribution, whether before a jury or before the court of international opinion, must be convincing and any action must be defensible.

Although advances in the life sciences are improving the tools available for bioforensics, Amerithrax also demonstrates the limitations of such innovations. Admittedly, bioforensics was in its infancy at the outset of the investigation. A 2017 Government Accounting Office report cites experts as stating that bioforensics at the time of Amerithrax was incapable of detailed characterization and comparative analyses, and whether the scientific findings would have withstood critical scrutiny in the courts is uncertain. Decker points out the scientific challenges facing Amerithrax at its outset, admitting that his job would have been much easier had he possessed today’s tools. He does not address what direction the case would have taken had the unique morphologies in the anthrax letter spores not been identified. Without that discovery of its link to RMR-1029, investigators may not have focused their attention on Ivins until much later, if ever. In that alternate universe, Amerithrax could have plausibly remained centered on its initial person of interest without ever casting serious suspicion on Ivins.

Neither a sterile official history nor a journalistic exercise, Decker’s book fills the gap in the history of the Amerithrax investigation. His book is an exemplary insider account of one of the most challenging investigations ever conducted by the FBI, and it raises important questions about the proper place of science in criminal probes. Decker’s story is all the more important given that few, if any, retellings are likely to come forth from individuals with his level of access and dedication to the truth.

Dr. Glenn Cross currently works for the Federal Bureau of Investigation and is a former deputy national intelligence officer for weapons of mass destruction, specializing in biological weapons. He also is the author of “Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975 to 1980.”

Disclaimer: The author is an employee of the U.S. government. All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis in this work are those of the author alone and do not reflect an official position or views of the U.S. government.

Read the whole story

· · · · · · · · · · ·

Death in the Air: Revisiting the 2001 Anthrax Mailings and the Amerithrax Investigation War on the Rocks

Scott Decker, Recounting the Anthrax Attacks: Terror, the Amerithrax Task Force, and the Evolution of Forensics in the FBI (Rowman & Littlefield,

Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin at the Helsinki Summit with U.S. President Donald Trump. Kremlin photo.

Don't miss stories. Follow Raw Story!

Former CIA director John Brennan explained Tuesday night how Russian intelligence manages to lure Americans into committing treason during an appearance on MSNBC’s “All In with Chris Hayes.”

Hayes noted that a statement Brennan made during a Congressional hearing in 2017 stuck with him over the years — and related it to a New York Times report that emerged Friday night confirming that the FBI opened an investigation into Trump’s ties to Russia prior to the appointment of special counsel Robert Mueller.

“You said ‘people who frequently go on a treasonous path do not know they’re on a treasonous path until it is too late,'” the host said, quoting the former CIA director. “How does that apply to what we’re learning about the concerns of people inside the FBI about the president’s behavior?”

“Russian intelligence services are adept and they will try to cultivate relationships with individuals and get individuals to do things they shouldn’t do and find them in, let’s say, compromising positions and use that as a way to intimidate these individuals to further cooperate with them,” Brennan said.

People who have relationships with Russians — or with others they didn’t even know were Russians — find themselves in positions where they “were doing things they should not have done,” the former CIA director said.

“It’s like reeling in a fish,” Brennan said. “You bring them home and you allow them to then do more and more things because they are ready in this predicament.”

The former intelligence chief noted that during his May 2017 testimony, he acknowledged that members of the Trump campaign who interacted with Russian officials may or may not have known they were being “reeled in” — but continued because they “wanted some type of quid pro quo.”

“That, I think, would be inexcusable, if they, in fact, were seeking some type of favor from the Russians to protect things that happened in the past or something in the future,” Brennan added.

Watch below:

Read the whole story

· · ·

John Brennan agrees: Trump is clear and present danger to US MSNBC

Former CIA director John Brennan concurs with former senior Justice Department official David Laufman's conclusion that the president is a clear and present ...

Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin at the Helsinki Summit with U.S. President Donald Trump. Kremlin photo.

Don't miss stories. Follow Raw Story!

Former CIA director John Brennan explained Tuesday night how Russian intelligence manages to lure Americans into committing treason during an appearance on MSNBC’s “All In with Chris Hayes.”

Hayes noted that a statement Brennan made during a Congressional hearing in 2017 stuck with him over the years — and related it to a New York Times report that emerged Friday night confirming that the FBI opened an investigation into Trump’s ties to Russia prior to the appointment of special counsel Robert Mueller.

“You said ‘people who frequently go on a treasonous path do not know they’re on a treasonous path until it is too late,'” the host said, quoting the former CIA director. “How does that apply to what we’re learning about the concerns of people inside the FBI about the president’s behavior?”

“Russian intelligence services are adept and they will try to cultivate relationships with individuals and get individuals to do things they shouldn’t do and find them in, let’s say, compromising positions and use that as a way to intimidate these individuals to further cooperate with them,” Brennan said.

People who have relationships with Russians — or with others they didn’t even know were Russians — find themselves in positions where they “were doing things they should not have done,” the former CIA director said.

“It’s like reeling in a fish,” Brennan said. “You bring them home and you allow them to then do more and more things because they are ready in this predicament.”

The former intelligence chief noted that during his May 2017 testimony, he acknowledged that members of the Trump campaign who interacted with Russian officials may or may not have known they were being “reeled in” — but continued because they “wanted some type of quid pro quo.”

“That, I think, would be inexcusable, if they, in fact, were seeking some type of favor from the Russians to protect things that happened in the past or something in the future,” Brennan added.

Watch below:

Read the whole story

· · ·

John Brennan agrees: Trump is clear and present danger to US MSNBC

Former CIA director John Brennan concurs with former senior Justice Department official David Laufman's conclusion that the president is a clear and present ...

AG Nominee Promises to Look Into Whether a Counter Intelligence Probe Was Improperly Opened Against Trump CNSNews.com

(CNSNews.com) - During his Senate confirmation hearing Tuesday, Attorney General Nominee William Barr promised to look into whether a counter intelligence ...

Is Devin Nunes in Trouble with Mueller?

Vanity Fair-14 hours ago

Months after his name largely disappeared from national headlines, Congressman Devin Nunes—one of the earliest and most vocal critics of ...

Mueller investigating Devin Nunes and Michael Flynn's meeting with ...

International-Salon-11 hours ago

International-Salon-11 hours ago

Devin Nunes: Report on Mueller inspecting pre-inauguration event a ...

Washington Examiner-4 hours ago

Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Calif., on Tuesday dismissed a report that said special counsel Robert Mueller is scrutinizing an event he attended with ...

Nunes: Daily Beast Report on Trump Hotel Breakfast Meeting Is 'Fake ...

International-Daily Beast-6 hours ago

International-Daily Beast-6 hours ago

Devin Nunes: Counterintelligence bombshell shows FBI leaders 'had ...

Washington Examiner-Jan 13, 2019

Rep. Devin Nunes, the top Republican on the House Intelligence Committee, said the New York Times' bombshell report on a ...

Nunes: FBI Probe into Whether Trump Worked for Russia Revenge for ...

International-Breitbart-Jan 12, 2019

International-Breitbart-Jan 12, 2019

Mueller is scrutinizing Devin Nunes' meeting with a convicted Trump ...

AlterNet-Jan 14, 2019

Special Counsel Robert Mueller is scrutinizing a meeting that included one of President Donald Trump's most prominent defenders, Rep. Devin ...

Mueller Probes an Event With Nunes, Flynn, and Foreign Officials at ...

International-Daily Beast-Jan 14, 2019

International-Daily Beast-Jan 14, 2019

Read the whole story

· ·

Next Page of Stories

Loading...

Page 2

The FBI should brush up on the powers of the chief executive.

The FBI took it upon itself to determine whether the president of the United States is a threat to national security.

No one had ever before thought that this was an appropriate role for the FBI, a subordinate agency in the executive branch, but Donald Trump isn’t the only one in Washington trampling norms.

The New York Times reported the astonishing news. “Counterintelligence investigators,” the paper writes, “had to consider whether the president’s own actions constituted a possible threat to national security.” U.S. presidents over the decades have made many foolhardy decisions that have undermined our security; never before have they been deemed a fit subject for an FBI investigation.

The proximate cause for the probe into Trump was his firing of FBI director James Comey, which the FBI considered both a potential crime and a national-security matter because it might shut down the investigation into Russian efforts to influence the 2016 election.

Even if they were shocked by the treatment of Comey, top FBI officials should have been able to quickly ascertain that the Russia investigation continued unimpeded — indeed, it is still ongoing today.

NOW WATCH: 'U.S. Trade Negotiations Continue Despite Shutdown'

If the Times reporting is correct, the FBI grew more suspicious of Trump’s conduct based on comments that have been widely misunderstood. Among the bill of particulars:

—During the campaign, he urged the Russians to hack Hillary Clinton’s email. Trump clearly meant this line sardonically, though.

—The GOP platform allegedly was softened toward Russia. Never mind that, as Byron York of the Washington Examiner has demonstrated, this didn’t actually happen.

—And in his Lester Holt interview after the Comey firing, Trump said that “this Russia thing with Trump and Russia is a made-up story.” The president added, it’s worth noting, that he knew firing Comey probably extended the investigation rather than shortened it.

More legitimately, agents were disturbed by Trump’s continual praise for Vladimir Putin. These comments were blameworthy, but not a federal offense.

The Times implies that foreign policy played into the FBI internal debate whether to investigate Trump. “Many involved in the case,” the paper reports, “viewed Russia as the chief threat to American democratic values.” That is an entirely defensible and perhaps correct view (China is the other candidate for the dubious distinction). But there is no warrant for the FBI letting it influence the momentous decision whether to investigate a president of the United States.

As part of the executive branch, the FBI should brush up on the powers of the chief executive. The president gets to fire subordinate executive-branch officials. He gets to meet with and talk to foreign leaders. He gets to make policy toward foreign nations. Especially important to the current investigation, he gets to say foolish, ill-informed, and destructive things.

If the president wants to tilt toward Russia (not that Trump really has, except in his words), he can. If he wants to butter up China’s dictatorial president during high-stakes trade negotiations, he can. If he wants to announce a precipitous withdrawal from Syria and make it slightly less precipitous in a fog of confusion, he can.

And the FBI should have nothing to say about it.

The Times story is another sign that we have forgotten the role of our respective branches of government. It is Congress that exists to check and investigate the president, not the FBI. Congress can inveigh against his foreign policy and constrain his options. It can build a case for not reelecting him and perhaps impeach him. These are all actions to be undertaken out in the open by politically accountable players, so the public can make informed judgments about them.

Perhaps the Times report is exaggerated, or the FBI has serious evidence of a criminally corrupt quid pro quo between Trump and Moscow that there’s no public indication of yet.

Otherwise, the Times story is a damning account of an offense against our political order, and not by Donald Trump.

© 2019 by King Features Syndicate

Read the whole story

· · ·

An alleged top drug-trafficker for Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán testified in federal court the infamous Mexican drug lord paid a $100 million bribe in October 2012 to Mexico’s then-President-elect Enrique Peña Nieto.

- Former top FBI lawyer James Baker under criminal investigation for media leaks Washington Examiner

- Former top FBI lawyer James Baker subject of criminal media leak probe, transcript reveals Fox News

- Former FBI General Counsel James Baker under criminal investigation CNN

- Ex-FBI general counsel faced criminal leak probe POLITICO

- Republicans request update on investigation into ex-FBI official accused of leaks | TheHill The Hill

- View full coverage on Google News

Transcripts detail how FBI debated whether Trump was 'following directions' of Russia

Posted: 6:32 AM, Jan 14, 2019 Updated: 1 hour agoBy: CNN

M.N.: A bunch of the Incompetent Obamanites, not the professional Counterintelligence officers. No wonder...

"I'm speaking theoretically. If the President of the United States fired Jim Comey at the behest of the Russian government, that would be unlawful and unconstitutional," Baker said.

"Is that what happened here?" Rep. John Ratcliffe, a Texas Republican, asked Baker.

"I don't know," Baker responded, before the FBI lawyer cut off additional questions on that line of inquiry.

M.N.: What are the facts indicating the "behest of the Russian government"? Present them in a safe, non-classified way. What was the thinking, the interpretation of these facts? What was the logical or the intuitive ("hunches") process of transforming the interpretations of these facts into the specific decisions? Etc., etc. This account is more consistent with the picture of the scared panicky little children who do not really understand what is going on rather than the high level FBI officers. This impression is also consistent with the other and well known facts of these people's (specifically Strzok and Page) immature, to put it very mildly, behavior.

Once, some years ago, in SJ airport, the FBI agents tried to provoke me by using some colorful but standard slurs. Go check your records, if you kept them. I will return their courtesy with passion and pleasure:

Miserable, pathetic, stupid, incompetent, brainless, treacherous little Fags (Straight or Gay, does not matter, still the same miserable, stupid, good for nothing, village idiots, FBI FAGS)-Robots-Idiots!

As long as you are in the FBI, this country will not have any luck.

Purge them!

Do not fuck with Mike. Bike with Mike.

____________________________________

In the chaotic aftermath at the FBI following Director James Comey's firing, a half-dozen senior FBI officials huddled to set in motion the momentous move to open an investigation into President Donald Trump that included trying to understand why he was acting in ways that seemed to benefit Russia.

They debated a range of possibilities, according to portions of transcripts of two FBI officials' closed-door congressional interviews obtained by CNN. On one end was the idea that Trump fired Comey at the behest of Russia. On the other was the possibility that Trump didn't have an improper relationship with the Kremlin and was acting within the bounds of his executive authority, the transcripts show.

James Baker, then-FBI general counsel, said the FBI officials were contemplating with regard to Russia whether Trump was "acting at the behest of and somehow following directions, somehow executing their will."

"That was one extreme. The other extreme is that the President is completely innocent, and we discussed that too," Baker told House investigators last year. "There's a range of things this could possibly be. We need to investigate, because we don't know whether, you know, the worst-case scenario is possibly true or the President is totally innocent and we need to get this thing over with — and so he can move forward with his agenda."

Following Comey's firing, the FBI opened a probe into Trump for possible obstruction of justice , as CNN has previously reported. Part of the impetus for the investigation, the New York Times first reported Friday, was whether Trump's actions seemed to benefit Russia.

The congressional transcripts obtained by CNN reveal new details into how the FBI launched the investigation into Trump and the discussions that were going on inside the bureau during a tumultuous and pivotal period ahead of the internal investigation and special counsel Robert Mueller's appointment.

Republicans view the officials' comments as evidence that top officials at the FBI were planning all along to investigate Trump and that the probe wasn't sparked by the Comey firing, according to a Republican source with knowledge of the interviews.

While the FBI launched its investigation in the days after Comey's abrupt dismissal, the bureau had previously contemplated such a step, according to testimony from former FBI lawyer Lisa Page.

Peter Strzok, the former FBI agent who was dismissed from Mueller's team and later fired over anti-Trump text messages, texted Page in the hours after Comey's firing and said: "We need to open the case we've been waiting on now while Andy is acting," a reference to then-acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe.

Page was pressed on the meaning of the message in her interview with congressional investigators, and she confirmed that the text was related to the Russia investigation into potential collusion.

Page told lawmakers the decision to open the case was not about "who was occupying the director's chair," according to a source. While FBI lawyers limited her answers about the text, she said the text wasn't suggesting that the case couldn't be opened with Comey as director.

"It's not that it could not have been done," Page told lawmakers. "This case had been a topic of discussion for some time. The 'waiting on' was an indecision and a cautiousness on the part of the bureau with respect to what to do and whether there was sufficient predication to open."

Portions of Page's interview were first reported by The Epoch Times.